How macroeconomic modelling contributes to achieving SDG 13

In 1972, participants of the Stockholm Conference imagined a world, where humanity acknowledges the central role of the environment for our well-being. 50 years later, we have reached several milestones in re-adjusting human-nature relations and shifting development agendas towards more sustainable pathways. However, despite landmark reports like the Club of Rome’s “The Limits to Growth”, economic policies and environmental protection largely followed separate trajectories. Thinking back, what would have been possible, if economic policies would have integrated climate risks 50 years ago? Would we be closer to “tackling urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts” (SDG 13)?

We think the likely answer is yes, but unfortunately decisionmakers back then did not have a tool that would have allowed them to embed the impact of climate risks in their economic planning. They also did not have a tool that would have enabled them to model different adaptation scenarios and choose the ones that would reduce economic risks or systematically plan towards decarbonisation of economies.

Luckily, we are now able to effectively integrate economic policy planning and climate action in a single coherent framework. This ensures climate resilient development by planning – not by chance. We are convinced that macroeconomic modelling is a powerful tool, which can bring science-based decision-making to life and align our imagination of a better life on this planet with sophisticated assumptions about future developments.

Macroeconomic modelling 101

Given that macroeconomic modelling does not ring a bell with everyone, we will guide you through the most important parameters you need to know. Generally speaking, one aim of macroeconomic modelling is to improve the basis of information available for policymaking. In the context of climate change, a key advantage of macroeconomic modelling is that it can unveil co-benefits of climate action for the economy and employment, and thus enables a long-term perspective for planning. The results of such modelling can highlight areas where investment in an adaptation measure can affect macroeconomic indicators – such as the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) or its employment rate – over the medium to long term. Hence, climate risk assessments and adaptation measures become part of national economic policy and lead the way towards climate resilient development pathways.

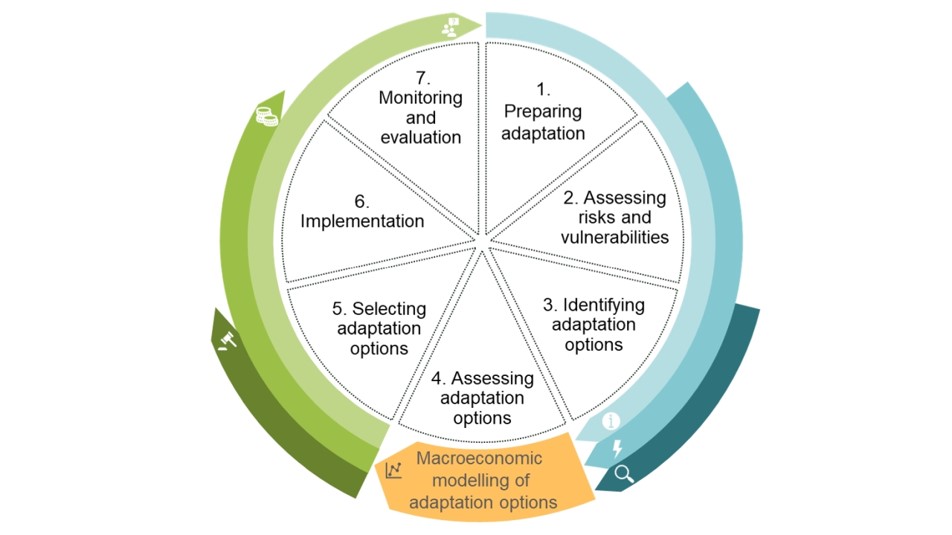

The policy brief ‘Macroeconomic Models for Climate Resilience’ published by the IKI-funded and GIZ-implemented project “Policy Advice for Climate Resilient Economic Development” (CRED) illustrates the benefits of macroeconomic modelling for the adaptation policy cycle.

We can divide the adaptation policy cycle into three phases as Figure 1 illustrates:

- Getting ready for climate risk management

- Modelling and evaluation of adaptation measures

- Enabling climate resilient development

Figure 1: Macroeconomic Modelling the Adaptation Policy Cycle. Source: based on ClimateAdapt.

Phase 1: Getting ready for climate risk management

The first phase lays the foundations for macroeconomic modelling. Here, the needs and political mandates for adaptation measures within a ministry are first established. Ideally, this results in a policy leadership role that supports the implementation of subsequent steps and ensures the coordination between participating stakeholders. The following step involves an analysis of the country’s climate risks and vulnerabilities, and assessing their economic impact. For this, we consider future climate scenarios and analyse past and current economic losses resulting from climate-related hazards. Eventually, we end up with a prognosis of the long-term development of economic losses. We conclude the first phase by identifying adaptation measures for macroeconomic modelling. These may include concrete investments in climate-resilient roads, drip irrigation in agriculture and much more. As this kind of analysis requires a lot of data, only the most relevant measures should be selected.

Phase 2: Modelling and evaluation of adaptation measures

In the second phase of the policy cycle, we do the actual modelling. The model covers a long time span, e.g. 30 years. Over this period, we can illustrate the development of key economic indicators, such as, GDP, sectoral productivity and the employment rate. To obtain a better idea of the economic impact of individual adaptation measures, we employ a hypothetical comparison scenario in which climate change does not occur. We then integrate the previously analysed climate risks into this comparison scenario. Thereby, we can model the long-term climate change impacts on the economy. These results raise awareness for the need to adapt to climate change. In the next step, we incorporate the adaptation measures into the modelling. By comparing the two scenarios, we can then estimate the economy-wide implications of individual adaptation measures. Essentially, we compare the scenarios ‘Climate change without adaptation’ and ‘Climate change with adaptation’. You can find examples of such modelling work in the sectoral policy briefs produced by the CRED project, e.g. with a focus on agriculture in Kazakhstan or on tourism and infrastructure in Georgia. Such analyses allow to make the business case for adaptation action by showing which measures benefit the long-term economy-wide development.

Phase 3: Enabling climate resilient development

In the third phase of the policy cycle, we select and implement the adaptation measures. The modelling results inform the selection of suitable adaptation measures. Moreover, based on the prior assessment of the economic impacts of different adaptation measures, it is possible to better justify the necessary budget decisions. Modelling results can also improve the monitoring and evaluation of adaptation measures, since these results already include indicators such as the employment rate, which can be used to assess the measures.

Benefits and challenges at a glance

One of the greatest benefits of macroeconomic modelling is also the most obvious: the economic impact of climate risks and adaptation measures is made visible and can then be used as input for national economic policy. Macroeconomic models also facilitate comprehensive risk assessments, which provide a more detailed overview of the social and economic impacts of climate-related risks.

One should be aware, however, that such a model is typically unable to portray the non-economic impacts of climate change – which include e.g., the loss of biodiversity. The sheer amount of data involved presents another difficulty. Comprehensive data sets are required on economic indicators and climate risks/damages, as well as cost-benefit analyses for the adaptation measures planned.

Despite the challenges involved in macroeconomic modelling, we want to stress that the continuous fine-tuning of the model is another major strength of this approach. Accordingly, economists are in regular exchange with various stakeholders and decisionmakers about which are the most effective adaptation approaches for a resilient economy. These dialogue processes are just as important as the actual modelling results since they help to fill the gap between climate adaptation and the economic policy planning.

Imagine the world in 2050

A better understanding of the economic risks of climate change propels the transition to decarbonisation and achieving net-zero emissions to avoid high-risk scenarios. Plus, unavoidable climatic risks can be better managed with macroeconomic models that integrate climate risk assessments and economic benefits of various adaptation measures. Thereby it becomes possible to not only imagine a world in which we achieve climate resilience (SDG 13.1), but one where we actively plan towards that goal. However, all planning is meaningless if those plans are not translated into action. Therefore: Let’s put the tools and knowledge that we have into practice. That way we can shape the future starting from today and make our vision of a climate resilient world the reality we live in.

Contact:

Sebastian Homm, Advisor, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

Global programme on climate resilient economic development (CRED)

Authors:

Sebastian Homm Advisor, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

Anne Weltin Junior Advisor, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

Nedim Sulejmanovic Intern, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH